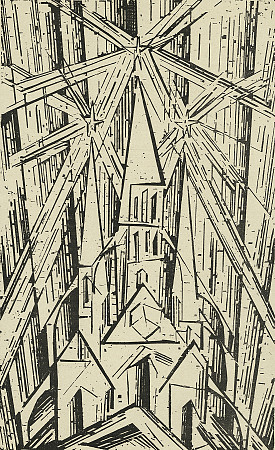

Lyonel Feininger (Illustration), Walter Gropius (Author) Manifesto and programme of the State Bauhaus, April 1919, with illustration “Cathedral” illustration by Lyonel Feininger, 1919

Lyonel Feininger (Illustration), Walter Gropius (Author) Manifesto and programme of the State Bauhaus, April 1919, with illustration “Cathedral” illustration by Lyonel Feininger, 1919 Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

Idea

The Bauhaus only existed for 14 years: from 1919 to 1933. Despite this, it became the twentieth century’s most important college of architecture, design and art. For political reasons, fresh starts had to be made repeatedly in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin, but under its three directors – Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – the college continued to develop further. The intention to rethink design from the bottom up and not to accept any traditional certainties not only opened the way to a fresh start in modern art, but also enabled the influence of the ‘Bauhaus experiment’ to continue right down to the present day.

This woodcut by Lyonel Feininger was included by Walter Gropius in the Bauhaus’s founding manifesto and programme in 1919. It shows a cathedral with a tower whose tip is surrounded by three stars – standing for the three arts of painting, sculpture and architecture – with the rays from them interlaced symbolically. All of the crafts and arts had already worked together on an equal basis even in the stonemasons’ lodges of medieval cathedrals. At the Bauhaus, the cathedral now stood for the total work of art that was to combine architecture, craft and art into an ideal unity. The Bauhaus was thus aiming to reunite the arts that had previously been separated in the academies in order to arrive at contemporary forms of art and architecture. As in the reform movements that had preceded the Bauhaus, what mattered was to find a response to industrialization and its effects. The artistic avant-garde that gathered at the Bauhaus wanted to become a force capable of changing society and hoped to form a modern type of human being and environment. In a transdisciplinary community of work, the ‘building of the future’ – and thus also the future itself – was to be conceived and created. This programmatic goal for the college was encapsulated almost like a slogan in the name ‘bauhaus’ (building–house). The challenge was how to turn these grand ideas for the future into a real educational course.

Despite the fact that goals and reality never quite coincided at the Bauhaus, the manifold influences to which the experiment gave rise have continued to the present day. Even more than the details of the solutions produced, what continues to be fascinating today is the exemplary attitude and the will to rethink things from the ground up. In this way, the Bauhaus, which only existed for 14 years, became the model for reform efforts in its period – and it continues to attract attention even today. ‘You can’t achieve that kind of resonance with either organization or propaganda,’ said Mies van der Rohe, the third and last Director of the Bauhaus. ‘Only an idea has the power to spread so widely.’